This week I had the privilege to attend the Sante Fe Institute’s conference in conjunction with Morgan Stanley entitled Risk: The Human Factor. There was quite the lineup of speakers, on topics ranging from Federal Reserve policy to prospect theory to fMRI’s of the brain’s mechanics behind prediction. The topics flowed together nicely and I believe helped cohesively construct an important lesson—rules-based systems are an outstanding, albeit imperfect way for people and institutions alike to increase the capacity for successful prediction and controlling risk. In the past on this blog, I have spoken about the essence of financial markets as a means through which to raise capital. However, in many key respects, financial markets have become a living being in their own right, and as presently orchestrated are vehicles where humans engage in continuous prediction and risk management, thus making the lessons learned from the SFI speakers amazingly important ones.

This notion of financial markets as living beings in SFI’s parlance can be described as a “complex adaptive system” and is precisely what SFI is geared towards learning about. While financial markets (and human beings) are complex adaptive systems, SFI is a multi-disciplinary organization that seeks to understand such systems in many contexts, including financial markets, but also in biology, anthropology, social structures, genetics, chemistry, drug discovery and all else where the concepts can be applied.

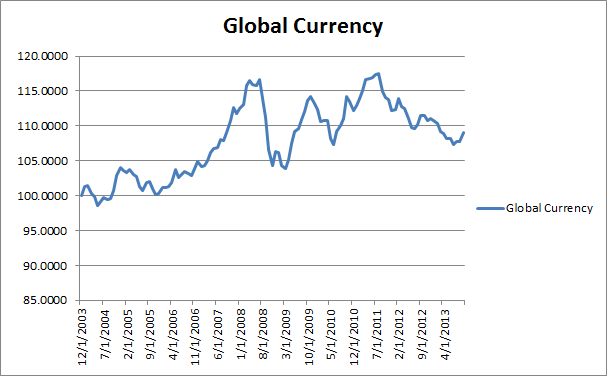

To highlight the multi-disciplinary nature of the event, John Rundle, one of the co-organizers of the event and a physics professor at the University of California Davis, with a special background in earthquake simulation and prediction introduced the theme for the day. Dr. Rundle presented results for his trading strategy founded upon his theories for earthquake prediction. The strategy was built upon asking the following question: can models for market risk be constructed that implicitly or explicitly account for human risk? Seems like things are off to a great start.

Some of the coolest, most interesting moments came during the Q&A sessions, where this year’s presenters, some past presenters, and many brilliant minds from finance including Michael Mauboussin, Bill Miller and Marty Whitman had the opportunity to engage each other on their theses, refining and expounding upon each other’s ideas. Sitting in the room and absorbing conversations like John Rundle speaking with Ed Thorp during an intermission about their own risk management perspectives and how to maximize the Kelly Criterion in investments was a surreal experience that I sadly cannot impart in this blog post, but I hope to channel the spirit in sharing some of the important ideas I learned. Further, I'd like to invite any of you readers out there to add your own thoughts in the comments below.

Let’s start with the first presentation and walk through the day together. In each subsection, I will give the presenter and their lecture title, followed by some notes from the lecture that I felt were relevant to my practical needs (this is not meant to be a thorough overview of each and all presentations). I will type up my notes from Ed Thorp’s presentation in its own blog post, for there seemed to be considerable interest from fellow Twitterers on that one lecture in particular.

David Laibson, Harvard University

Can We Control Ourselves?

Does society have the capacity to prepare for demographic change? Experiments consistently show that people want the right thing, particularly when the question is presented as one of future choice. However, when faced with the very same choice in the present, we fail to make the right decision; the very same decision we would make for longer-term planning purposes. There is a behavioral reason for this: we want the right thing, but right now gets the full brunt of the emotional psychological weight, while planning is not nearly as influenced by the emotional element. As a result, humans have a knack for making terrific plans, with no follow-through.

There is a neural foundation for this, as we have 2 systems (this is derivative of the idea presented in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast, and Slow).

- The planning and focused system

- The dopamine reward system based on immediate satisfaction

How can we help people follow-through on their goals in planning as it pertains to saving for retirement?

- We can change the system from opt-in to auto-enroll, also known as the Nudge. Nudge is based on an idea presented by behavioral economists, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in the book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

- We can use what’s called “active choice” and punish inaction, such that people must call and make a decision about their savings, rather than delaying it.

- Make enrollment quicker by taking away the 30 minute paperwork barrier.

Which is most effective:

- 40% participate with opt-in

- 50% participate with an easier process

- 70% enroll with active choice

- 90% participate with a nudge

To that end, we were presented with information that showed people recognize self-control problems and opt for less liquid savings options if given the choice, EVEN IF the returns are exactly the same. That is, people acknowledge their inability to control the itch to break their well-made plans.

Vincent Reinhart, Managing Director and Chief U.S. Economist at Morgan Stanley

FED Behavior and Its Implications

- Our paradigm for monetary policy:

- We have an expectation for the path of the economy and the Fed sets policy to meet that expectation

- The difference in policy over 2 successive actions follows a random walk. You can only acquire so much new information about the economy over the course of six weeks, making decisions based primarily on prior knowledge.

- The puzzle of persistence:

- Despite the random walk on decision-making, a chart of the Fed Funds Rate doesn’t actually follow a random walk. It is a persistent path, whereby if the interest rate went down the prior month, it is more likely to go down again in the present month.

- The source of persistence:

- If there is persistence, and policies are predictable, then there should be ways to generate returns off of it. Prices then would be drive to a fundamental value by arbitrage. However, in central banking there is no arbitrage opportunity, because the mechanisms are confined to just the Fed and commercial banks, with no open market participation.

- While many talk about recent actions being “unprecedented” this is unequivocally not true. These actions are very consistent with central bank behavior—QE and its ilk are balance sheet actions.

- Previously the Fed had a larger balance sheet as a % of GDP in the mid-1940s.

- Policy decisions are made by committees:

- Larger committees lead to less variance

- The right model to think about this is the committee as a jury, not a sample of policy options. The committees deliberate and take the best argument.

- There is an hierarchy of status in the Fed, including titles and media-friendliness that lead to greater degrees of influence from some members, over others. This leads to the perfect setting for herding outcomes.

- Thus the random walk fails.

- Why have we not had a strong bounce-back from this recession?

- Milton Friedman talks of “plucking on a string” whereby a big drop should lead to a big bounce.

- There are serious problems with this analogy:

- An equal percent decline, and rise will not get you back to your starting point. (1-x) * (1+x)=1-x²

- In a “pluck” in physics it never gets you back to your starting point, as there is a transfer of energy in the transition from down to up.

- The observation that recessions should work like a plucked string were misguided, since they focused on a small sample size ONLY covering 1946-1983, looking neither at the prior 100 years, or updating for the past 30 years.

- After severe financial crisis, recoveries are consistently very poor.

- What is the best paradigm for decision-making?

- Rules consistently do better than discretion.

- From June to December that conversation has started to change, and QE3 is far more analogous to a rules-based system. However, we don’t yet have enough information on when or how the rules will end.

I had the opportunity to ask a question, so I asked whether NGDP targeting would be such an optimal rules-based system, and if QE3 was something akin to NGDP. Reinhart answered that while QE3 does get us closer to a rules-based system it is not like NGDP. He further asserted that he wouldn’t necessarily be in favor of NGDP targeting, and that a system of NGDP targeting would be an implicit, under-the-radar way for the Fed to let the market know it will slacken on the inflation coefficient of its dual mandate.

Philip Tetlock, University of Pennsylvania

The IARPA Forecasting Tournament: How Good (Bad) Can Expert Political Judgment Become Under Favorable (Unfavorable) Conditions?

In the 1980s, the government funded a study looking into how well experts predict global events, called the IARPA Forecasting Tournament. Today, this experiment is being recreated, with a focus on forecasting global events of interest to the US government. The experiment uses the Brier Score, first developed for weather forecasters, in order to gauge accuracy. The best Brier score is 0, a dart-throwing chimp registers a 0.5 and the worst possible score is 2.

Types of prediction ceilings:

- Perfectly predictable events (100% ability to predict)

- Partly predictable events

- Perfectly unpredictable

In the first year of the tournament, the average score in the baseline was 0.37, better than the chimp, but not quite perfect. The best algorithms score 0.17 and sit 0.29 units away from the truth.

In the top performing groups of participants had the following traits in common (note: collaboration was welcomed and fostered by the moderators). I’m injecting my opinion here, but I find these to be very important goals for any organization in attempting to participate in an arena where prediction is important (in this case, for investors the lessons can be particularly apt).

- The best participants

- Collaboration whereby people actually work together and deliberate about their predictions.

- A training in probabilistic reasoning a la Kahneman’s ideas in Thinking, Fast and Slow

- Combine the training and teamwork

- Elitist aggregation methods whereby more weight is added to the best predictors/experts in certain areas when combining predictions to make one uniform “best” effort at prediction.

Two lessons/observations:

- Teams and algorithms consistently outperform individuals.

- Forecasters consistently tend to over-predict change.

Elke Weber, Columbia University

Individual and Cultural Differences in Perceptions of Risk

In finance we think of risk as volatility. Culturally however, risk is a parameter, not a model. Risk is therefore subjective and intuitive on an individual level. Further, when faced with extreme outcomes, emotion becomes an increasingly more powerful force on perceptions of risk. It is the perceptions of risk that drive behavior, and these perceptions exist on a relative, not absolute scale. Humans are biologically wired to that end.

Weber’s Law (not Elke Weber, an earlier Weber): the differences in the magnitude required to perceive two stimuli is proportional to the starting point. i.e. all differences are measured by a relating the new position to the original.

Familiarity actually works to reduce perceptions of risk, but not risk itself. Experts in a certain field tend to underestimate risks due to familiarity. Return expectations and perceived riskiness predict choice, NOT the expectation of volatility (i.e. risk is perceived on a relative scale, not through the formulaic calculation of volatility).

Cultural differences—Shanghai vs. US MBA students:

- The collectivist nature of Chinese culture mitigates the damaging effects of risk gone awry. This is called the “cushion hypothesis.” As a result, Chinese MBA students tend to be more risk-seeking.

- Families in China tend to help their members far more than in the US when it comes to transferables (people help mitigate the risk of a money-based decision gone wrong, but cannot do so on risky health decisions).

- Risk was consistently based on relative perceptions of risk within the context of the safety net.

In the Animal Kingdom, the most base way to perceive risk is through experience. Small probability events tend to be underweighted by experience, but overweighted by perception.

- When small probability events hit, the recency bias makes people overweight the chances it will happen again.

- Experience metrics tend to be more volatile in how they perceive risk.

- Studies show that crisis (like the Great Depression) do have an enduring impact on how risk is perceived.

I had the opportunity to ask Dr. Weber a question. I asked her about the point that familiarity tends to lead people to overlook risk, and how that can be reconciled with the value investing concept of sticking to a core competency? If through focusing on a core competency, rather than mitigating risk, investors were increasing it. Dr. Weber rightly observed that focusing on a core competency does have some distinctions with familiarity in that the idea is to work in areas where one has the most skill, but that there could very well be such a connection. In fact, she thought my question to be “very interesting” and worth further observation.

Nicholas Barberis, Yale University

Prospect Theory Applications in Finance

Can we do better in financial markets replacing expected utility with prospect theory?

Some core elements of prospect theory in finance:

- People care about gains and losses, not absolute levels of performance

- People are more sensitive to losses than gains

- People weight probabilities in a non-linear way (i.e. they overweight low probability, underweight high probability).

There is little support for beta as a predictor of returns. Prospect theory instead focuses on the idea that a security’s (or indices) own skewness will be priced based on the scale of the left or right tail.

- In positively skewed stocks people tend to overweight small chances of big success, and thus get low returns as a result (and vice versa).

- As a result, big right skewness should have a low average return and this is proven in IPOs, out of the money options, distress stocks and volatile stocks.

- Probability weighting in prospect theory is a better predictor of returns.

- If people are loss averse, as prospect theory holds, the equity premium will be higher.

- Overall, the market is negatively skewed, thus probability weighting produces a higher equity risk premium overall.

The Disposition Effect – people sell stocks that have gone up far quicker than stocks that have gone down.

- Do people get pleasure/pain from realizing gains/losses? i.e. realization utility. The model predicts that:

- There is greater turnover in bull markets as a result.

- There is a greater propensity for selling above historical level of highs.

- There is a preference for volatile stocks.

- Momentum is also preferred.

Gregory Berns, Emory University

When Brains are Better than People: Using fMRI to Predict Markets

Dr. Berns started with a history of using blood pressure in order to ascertain where/how/why certain stimuli impact the brain. Today we can use fMRI in order to clearly see ventricular activity and this provides a nice window into how the brain works. Blood flow to regions of the brain change based on which part of the brain is active/engaged at any given point in time. Animals in the wild that are most adept at prediction can survive far better in changing environments than those who cannot.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, dopamine is not directly correlated to pleasure. Dopamine in fact is correlated to the anticipation (i.e. the delta) of pleasure. It is the changes in dopamine levels which lead to decisions. Dr. Berns showed a fascinating slide using the corking and drinking of a fine wine to illustrate this point. It is in the moment of opening the bottle of wine that people experience the dopamine release, rather than during the pouring of the glass or taking the first sip.

Dr. Barberis had mentioned fMRI and its application to measuring the disposition effect and here Dr. Berns confirmed and illustrated. There are three explanations for why the disposition effect happens:

- People’s risk preference

- The realization utility (i.e. people like realizing gains, loathe realizing losses)

- Mean reversion

Using fMRI, we can see that there are different approaches to the disposition effect depending on how and where the brain reacts (note: boy do I wish I had these slides, because the images are amazing in highlighting the effects). People tend to fall into 2 camps—those who are influenced by the disposition effect, and those who are not. fMRI shows that in those who ARE influenced by the effect, the blood flow is most active in the stem of the brain, the area where dopamine is released. In those who are NOT impacted by the disposition effect, there is brain activity in a much broader portion of the cerebrum (the bigger part of the brain).

This effect was studied using fMRI in 2 contexts involved in understanding prediction.

- Music: people were given fMRI while many songs were played, analyzing where in fact the brain was triggered. Only years later, when one of the obscure songs became a hit did Dr. Berns check his data and it showed that this hit song actually did in fact induce a higher degree of activity in the brain. Brain data correlated more with the likeability of success.

- Markets: MBA students were given fMRI while simulating the ownership of stocks into earnings. Their reactions were tested for beats or misses. The tests were demonstrative of the fact that negative surprises hurt far more than positive ones feel good. This could be a major explanatory force behind the disposition effect.

Please note: I apologize for any formatting errors. This post was drafted in Word and did not transfer very cleanly at all into the Squarespace format. In the interest of sharing the ideas in a timely mannger, I will go ahead and publish before I have the chance to clean up all the spacing, tabbing, etc. Please enjoy the content and try to look past the messy spacing.