The Rise and (Inevitable) Fall of Bitcoin

/Bitcoin is receiving much attention these days for its parabolic ascent. The attention seems to stem from people’s concerns with monetary policy and the growing disdain with government intervention and oversight, generally speaking. It is no coincidence that Bitcoin’s surge this year corresponds with the growing public backlash over these large issues. To that end, Bitcoin is a great story, but is it a great idea?

A Bitcoin Economy?

The textbook definition of money holds that it must be a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. Colloquially when many say "currency" they in fact mean "money," especially with regard to Bitcoin. We will ignore the argument as to whether Bitcoin is an effective store of value given its volatility and focus purely on the philosophical question of whether Bitcoin makes sense as money. For Bitcoin to truly emerge as “money” there must be an economy with the actual transfer of goods built on top of it. In such an economy, there will be some people who “save” money. This means that some will put off consumption today for the capacity to consume at a future date.

It’s hard to project exactly how much commerce will be done on Bitcoin, or how big the “economy” will be, but we do know that venture capitalists like Fred Wilson are investing in the Bitcoin ecosystem, and Marc Andreessen has expressed interest in following suit. Further, the US government’s arrest of the Silk Road founder and crackdown on the black market drug trade via Bitcoin could help lend great legitimacy to the broader Bitcoin economy. Given the evolution of credibility and interest amongst venture capitalists to grow an economy on Bitcoin, we can presume that Bitcoin’s price today reflects a belief that an economy will in fact be able to develop.

The Monetary Mechanics of Bitcoin

Before we can answer whether Bitcoin can work as “money,” let’s talk about the mechanics behind it (and by mechanics, we will ignore the cryptography and security element and focus purely on the monetary mechanics). Here are the mechanics for how Bitcoins are created:

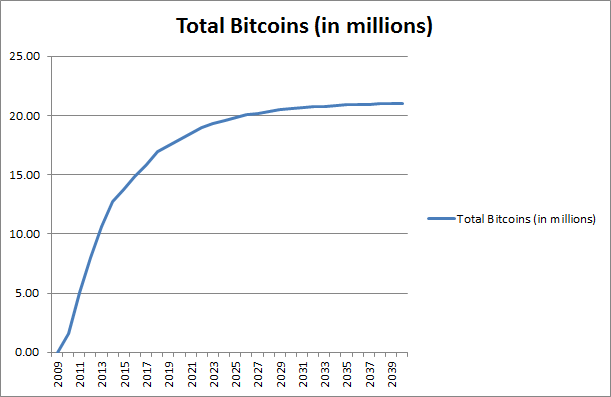

The reward for solving a block is automatically adjusted so that roughly every four years of operation of the Bitcoin network, half the amount of bitcoins created in the prior 4 years are created. 10,500,000 bitcoins were created in the first 4 (approx.) years from January 2009 to November 2012. Every four years thereafter this amount halves, so it will be 5,250,000 over years 4-8, 2,625,000 over years 8-12, and so on. Thus the total number of bitcoins in existence will never exceed 21,000,000.

With this informatino, we can plot exactly what the money supply of Bitcoins will look like over time:

As such, we know that somewhere around 2040, the entire supply of Bitcoins will have been “created” and that no new incremental supply of will emerge from that point, onward.

The next important feature of Bitcoins that’s important to understand is the “granularity” of the currency. As they are constructed, each Bitcoin can be broken down into denominations of up to 8 decimal places (with 0.00000001 BTC being the smallest denomination). The currency was created this way, so that as Bitcoins increase in value, people are able to make purchases with fractions of the increasingly valuable coinage, rather than needing to use whole things at a time.

Lastly, and related to the idea of granularity is the deflationary bias embedded in Bitcoins, as explained by the Bitcoin community itself:

Because of the law of supply and demand, when fewer bitcoins are available the ones that are left will be in higher demand, and therefore will have a higher value. So, as Bitcoins are lost, the remaining bitcoins will eventually increase in value to compensate. As the value of a bitcoin increases, the number of bitcoins required to purchase an item decreases. This is a deflationary economic model.

Here’s how the Bitcoin community explains this problem:

Worries about Bitcoin being destroyed by deflation are not entirely unfounded. Unlike most currencies, which experience inflation as their founding institutions create more and more units, Bitcoin will likely experience gradual deflation with the passage of time. Bitcoin is unique in that only a small amount of units will ever be produced (twenty-one million to be exact), this number has been known since the project's inception, and the units are created at a predictable rate.In fact, infinite divisibility should allow Bitcoins to function in cases of extreme wallet loss. Even if, in the far future, so many people have lost their wallets that only a single Bitcoin, or a fraction of one, remains, Bitcoin should continue to function just fine. No one can claim to be sure what is going to happen, but deflation may prove to present a smaller threat than many expect.Also, Bitcoin users are faced with a danger that doesn't threaten users of any other currency: if a Bitcoin user loses his wallet, his money is gone forever, unless he finds it again. And not just to him; it's gone completely out of circulation, rendered utterly inaccessible to anyone. As people will lose their wallets, the total number of Bitcoins will slowly decrease.Therefore, Bitcoin seems to be faced with a unique problem. Whereas most currencies inflate over time, Bitcoin will mostly likely do just the opposite. Time will see the irretrievable loss of an ever-increasing number of Bitcoins. An already small number will be permanently whittled down further and further. And as there become fewer and fewer Bitcoins, the laws of supply and demand suggest that their value will probably continually rise.Thus Bitcoin is bound to once again stray into mysterious territory, because no one exactly knows what happens to a currency that grows continually more valuable. Many economists claim that a low level of inflation is a good thing for a currency, but nobody is quite sure about what might happens to one that continually deflates. Although deflation could hardly be called a rare phenomenon, steady, constant deflation is unheard of. There may be a lot of speculation, no one has any hard data to back up their claims.That being said, there is a mechanism in place to combat the obvious consequences. Extreme deflation would render most currencies highly impractical: if a single Canadian dollar could suddenly buy the holder a car, how would one go about buying bread or candy? Even pennies would fetch more than a person could carry. Bitcoin, however, offers a simple and stylish solution: infinite divisibility. Bitcoins can be divided up and trade into as small of pieces as one wants, so no matter how valuable Bitcoins become, one can trade them in practical quantities.In fact, infinite divisibility should allow Bitcoins to function in cases of extreme wallet loss. Even if, in the far future, so many people have lost their wallets that only a single Bitcoin, or a fraction of one, remains, Bitcoin should continue to function just fine. No one can claim to be sure what is going to happen, but deflation may prove to present a smaller threat than many expect.

Why does all this matter and what am I getting at?

Historically there have been points in time where the propensity to save (and thus not spend) has outstripped the supply of currency available to be saved, thus choking off the flow of commerce. This is a big part of what happened in the Great Depression and is something that both Keynesians and Monetarists alike agree on. When countries “left” the gold standard, they effectively devalued their currency all at once (and it's no coincidence that the recovery from the Great Depression started with such a devaluation). This similar mechanical move has happened in the floating-currency regime whereby countries who peg their currency to a foreign currency (like Argentina’s peso pegged to the dollar), must abandon the peg with a devaluation in order to protect their currency.

What happens when too much of Bitcoin’s supply gets stashed as savings? Granularity provides a built-in answer. 1 bitcoin will be divided by 10 in its purchasing power (note: 0.1 Bitcoins is presently known as a centibitcoin). This is how spending and commerce will then return to the Bitcoin economy. The Bitcoin community argues that this will be a slow, “gradual deflation,” which is “unheard of” in world history. There is a reason for this: gradual deflation is a paradox that simply does not and cannot exist.

Remember above I told you I would eventually get to why theory and practice differ once savings exceed a certain level, and prices rise? I didn’t forget. Theory and practice diverge because theory presupposes a certain kind of human rationality that simply does not exist. When the price of a currency itself starts to rise, and supply starts to get scarce, instead of prior savers now spending money and solving the problem of too little circulating money, reality has time-and-again demonstrated that people who previously were not savers, and were engaged in commerce, see that more money was made by saving money than investing it. In response, prior commercial actors decide they too can make more money by hoarding money than they can by investing it, and upon that realization, they too turn into incrementally new savers. John Maynard Keynes dubbed this "The Paradox of Thrift" and the incorporation of paradox in the title is self-explanatory here. This positive feedback loop of saving begetting more saving continues until some kind of breakpoint is reached. This breakpoint is either a devaluation or a complete collapse in an economy, but either way, it is not and never has been pretty.

Considering Bitcoins are the ultimate fiat currency, backed by neither a hard asset, nor the capacity to tax, faith in the currency is immensely important, but also far easier to destroy than build up. This harkens back to Warren Buffett’s wise observation that “it takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” Once trust is lost in Bitcoin, it will be impossible to make it back.

Again, why does it matter?

Since I am speaking about this decline as inevitable, and obvious, let me explain why I think this even warrants conversation in the first place. I think Bitcoin is a fascinating experiment that will eventually have considerable value to help improve our knowledge of monetary systems, and to help dispel some of the myths that have built up in some recently popular economic circles. With the crisis, “hard-money” like the gold standard has become a popular “solution” despite the fact that we know both empirically and theoretically exactly how and why they don’t, won’t and never could work. Paul Krugman has tried to explain this problem with his explanation of the Capitol Hill Baby-Sitting co-op and Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry has highlighted this connection with Bitcoin, but considering the ideological nature of some of these questions, such proof will never be taken as positive. Bitcoin will eventually show us this reality in real-time.

The second source of my interest in Bitcoin is the role of feedback loops and reflexive processes in markets. George Soros’ Alchemy of Finance is one of my favorite market philosophy books and one I am a believer in. The essence of Soros’ “General Theory of Reflexivity” holds that markets are driven by feedback loops whereby prices influence the course of events, which influence prices, which in turn influence the course of events. I’ll let Soros further explain:

Feedback loops can be either negative or positive. Negative feedback brings the participants’ views and the actual situation closer together; positive feedback drives them further apart. In other words, a negative feedback process is self-correcting. It can go on forever and if there are no significant changes in external reality, it may eventually lead to an equilibrium where the participants’ views come to correspond to the actual state of affairs. That is what is supposed to happen in financial markets…...By contrast, a positive feedback process is self-reinforcing. It cannot go on forever because eventually the participants’ views would become so far removed from objective reality that the participants would have to recognize them as unrealistic. Nor can the iterative process occur without any change in the actual state of affairs, because it is in the nature of positive feedback that it reinforces whatever tendency prevails in the real world. Instead of equilibrium, we are faced with a dynamic disequilibrium or what may be described as far-from-equilibrium conditions. Usually in far-from-equilibrium situations the divergence between perceptions and reality leads to a climax which sets in motion a positive feedback process in the opposite direction. Such initially self-reinforcing but eventually self-defeating boom-bust processes or bubbles are characteristic of financial markets, but they can also be found in other spheres.

Understanding and spotting feedback loops in financial markets is one of the most important things an investor can do. Feedback loops are one of the sources of my interest in the Santa Fe Institute and its work on markets as a complex adaptive system (see my recent interview with Michael Mauboussin which spends some time on feedback loops). In fact, feedback loops are one of the telltale features of complexity. It is my operating hypothesis that Bitcoin is one such “positive feedback process” which will first lead to a spectacular risein prices, that will ultimately reverse and crumble into an even more remarkable decline.

As it stands today, per my thesis, Bitcoin’s “rise” should be in the early stages. This rise has been fueled by a combination of speculation and the promise for the development of actual commerce on Bitcoin. The adoption of broader uses for the currency will be the catalyst for the next stage of ascent. I’m not sure how far Bitcoin can go on the way up, nor am I sure exactly when the inflection point from rise to fall will occur, but one thing I am fairly certain of is that when the fall comes, it will be swift and violent. In the end, it's success will be its own demise. As they say, “what goes up on an escalator goes down on an elevator” and I would not want to be the one left holding the proverbial bag on the way down.