The Profit Margin Debate: A Look at Capitalism and Competition

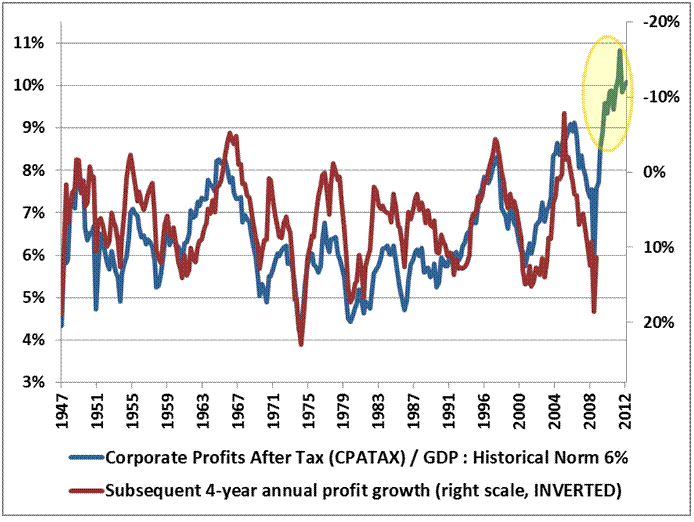

/Over the past two years there’s been a lot of talk about the mean-reverting nature of margins as a crucial source of the market’s “overvaluation” today. John Hussman and Jeremy Grantham have been two vocal advocates of this point. Here is Hussman’s chart to that effect:

In this debate, Bulls have pointed out a relevant counterpoint: that mean reversion can be to the trend, which has been higher due to more capital lean businesses, greater productive efficiencies, and international diversification, rather than simply to the longer-term average (here's a good post from Joe Wiesenthal which covers this point and more). This trend/mean distinction is important, for a reversion to trend would imply margins still move higher over time, albeit only after a move back to and most likely beneath the more recent trendline.

Mean Reversion in Markets

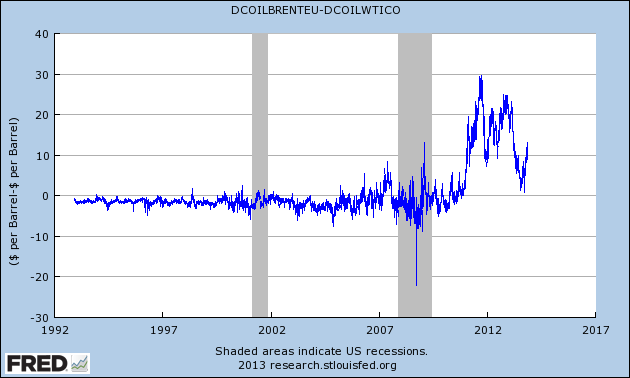

Mean reversion is a powerful force in markets. One of the reasons why it works so neatly in is that when certain spreads divert from their long-run means, there is an economic incentive in the form of arbitrage for position takers to drive the spread back down to its normal level. An anecdote would be helpful. The following is a chart of the spread between West Texas Intermediate (WTI) Crude Oil (ie the “American” oil supply) and London Brent Crude Oil (ie the rest of the world’s oil supply):

We can see that over the long run, this spread exists within a relatively narrow channel; however, something happens in 2011 that sends the price of London Brent shooting upward relative to WTI. We’ll forget about why and focus on how this spread ultimately reverted back to its normal confines (though it does seem to have perked up again). While there are logistical challenges in sending crude from North America to Europe and vice versa, when the price of oil gets too high in one place relative to another, arbitrageurs can make free money simply by buying oil where it’s cheap and selling it where it’s too high. This is the definition of riskless profit. As more and more arbitrageurs engage in this activity, what is a large spread gets whittled down until there is no more “free lunch” as they say. This is how efficient capitalist markets work.

Capitalism, Economic Profit and Competition

In the latest GMO Commentary, Ben Inker makes the following point about margins, market valuation and corporate investment: “The pleasant way we could be wrong is if the U.S. is about to embark on a golden age of corporate investment and economic growth that will gradually compete down the current return on capital such that overall profits manage to grow decently as the P/E of the stock market wafts slowly down.” What I find ironic is that corporate investment is the most common way margins can and do come down in capitalism, therefore, the most likely way for GMO to be right requires that they are wrong. Let me explain.

In a capitalist system, economic profit is not supposed to exist. Economic profit is the difference between returns on investment and the cost of capital for a business. When economic profit does exist, it is supposed to be followed by a period of economic loss, such that over a cycle, there is no economic profit. This is where the idea that margins mean revert comes from. Here’s Wikipedia’s explanation for how economic profit results in competition and no winners (ie excess profiteers) over the long-run:

Economic profit does not occur in perfect competition in long run equilibrium; if it did, there would be an incentive for new firms to enter the industry, aided by a lack of barriers to entry until there was no longer any economic profit. As new firms enter the industry, they increase the supply of the product available in the market, and these new firms are forced to charge a lower price to entice consumers to buy the additional supply these new firms are supplying as the firms all compete for customers. Incumbent firms within the industry face losing their existing customers to the new firms entering the industry, and are therefore forced to lower their prices to match the lower prices set by the new firms. New firms will continue to enter the industry until the price of the product is lowered to the point that it is the same as the average cost of producing the product, and all of the economic profit disappears. When this happens, economic agents outside of the industry find no advantage to forming new firms that enter into the industry, the supply of the product stops increasing, and the price charged for the product stabilizes, settling into an equilibrium.

This is good explanation, but I have presented it in the form of an oversimplification. Some kinds of companies are able to generate economic profit for long periods of time. These are the so-called quality companies with a moat (aka a sustainable competitive advantage) that Warren Buffett looks for. Since such firms are the rare exception, not the rule, it’s worth studying them and learning about the traits they share. This is something I do on a regular basis, though for the purposes of this essay, it’s a digression. I bring up this point because considering how rare such firms are, it’s safe to apply the concept of zero economic profit to the economy at large, and in doing so, assuming that margins do in fact mean revert.

In essence, high profit margins revert to the mean much the same way as the spread between WTI and London Brent Crude Oil, though the subtle differences are important. Whereas the WTI/Brent spread is brought down with arbitrageurs, the economic profit of high margins is brought down with entrepreneurs. When entrepreneurs see high profit margins, they see an opportunity to undercut those margins, and in doing so, capturing some of the profits for themselves. However, entrepreneurs can’t buy something and sell it elsewhere to capture this profit opportunity. They are called entrepreneurs as distinct from arbitrageurs because they actually have to engage in the “process of identifying and starting a business venture, sourcing and organizing the required resources and taking both the risks and rewards associated with the venture” (the definition of entrepreneur from Wikipedia).

To paraphrase, in order to capture the excess economic profit born of a too high profit margin, entrepreneurs need to raise capital, they need to make tangible investments in building the infrastructure of a business, and they need to hire people on the ground to make the business work. Simply put, margins don’t just go down, they get competed down and eroded over time through factors and forces that actually improve the economy at large, with the benefit at the end of the day being lower prices and better supply available for end consumers. This reversion in margins is always a process, never a one-off event, and it surely happens faster in some areas than others (Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma is a great example of the forces of competition and innovation in the rapidly evolving hard disk drive industry, see my post on The Essential Mental Model for Understanding Innovation).

Two Tales of Margin Erosion Today

Sometimes these entrepreneurs are startups with a cheaper, more scalable way of capturing the margin, and other times they are large competitors with lower margins who see an opportunity to grow their own business. Two anecdotes would be helpful. Let me note, for the purposes of these comparisons I’ll use only operating margins.

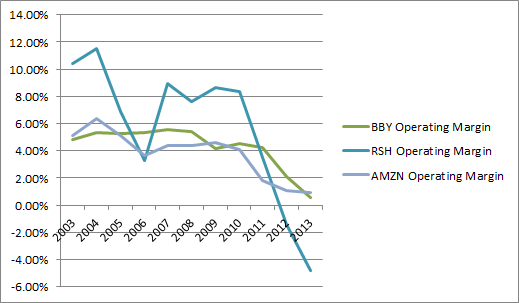

First is the case of RadioShack losing to Best Buy who in turn is losing to Amazon (it’s worth mentioning that Circuit City would be a nice addition to this chart, for it was competed into bankruptcy).

In some ways Amazon is not the perfect example, because its own margins are virtually unprofitable, but if we can see past that for a second it becomes clear why they are a fine example. RadioShack started with the highest margins of the bunch, but the longer Best Buy and Amazon stayed beneath them in margin, the more pressure there was building on RadioShack’s own business model to cut prices. Sadly for RadioShack, the company doesn’t have the infrastructure to compete on today’s playing field. While Best Buy held up admirably during the initial assault on RadioShack, we see clear signs that Amazon’s own low-margin model has been pulling Best Buy down with it.

How was Amazon able to drive the margins down of some of its biggest competitors (note: this happened in books with Border’s and Barnes and Noble having experienced Amazon’s rath before the consumer electronics companies)? They did this with massive amounts of investment. If you total Amazon’s investments over the past 5 years (capital expenditures + acquisitions + technology and content) you see that Amazon invested $21.1 billion. Compare this to Best Buy and RadioShack’s combined market cap of $13.5 billion and you can see why Amazon is a feared competitor. Again, it’s important to point out: Amazon was able to drive down Best Buy, RadioShack and Circuit City’s margins, much to the detriment of those companies, one of whom no longer exists and another of which is on the brink. In doing so, Amazon experienced tremendous growth in its own revenues of about 33% compounded over the past 5 years, all resulting from the company investing substantial sums of money and hiring a whole lot of workers. This is how capitalism is supposed to work.

Some might counter that this obviously won’t end well for the economy too, because Amazon makes 0 profit and any multiple of 0 is inherently 0 (ie 0 profit for the S&P multiplied by an average P/E of 15 equals $0). My counter would be a) Amazon could make a whole lot more money than they do, though we can never be sure exactly how much, but they choose to invest in future growth instead; and, b) that’s why I have this next example for you.

Here are Apple and Samsung’s respective operating margins over the past either years:

Apple wowed the world with its innovative iPod, iPhone and iPad. This trifecta launched Apple’s operating margins up from a puny 3.94% in 2003 to a high of 35.3% in 2011. The problem for Apple was that it’s profit margins became too juicy. They were so juicy they were practically begging competitors to steal some of their profits, and in the chart above, we can see clearly how as Apple’s margins fall from peak levels, Samsung’s shoot up. Up to this point, Samsung was only a bit player in the handheld phone business, and did most of their business in more commoditized, low-margin consumer electronics like TVs. With such a huge opportunity to undercut Apple in price and to improve their own margins in doing so, Samsung jumped in with great success. While Apple’s margins took a hit in the past year, their revenues continued to grow, as Samsung’s revenues surged (Apple’s revenues grew 9.2%, while Samsung registered 22% yoy growth). All in all, the size of the smartphone market pie grew tremendously over the past year, though the margins earned by its earliest, most profitable player declined. Meanwhile, both in aggregate and individually, Apple and Samsung were tremendously profitable.

Macro Applications of Micro Lessons

If we compare this to GDP and corporate profit margins, the GDP (ie smartphone market size) increased tremendously, the aggregate profits earned also increased, but the average margin across the market dropped. This is a win/win for the market, for consumers and for the competitors, though is not necessarily ideal for some of the status quo players. Again though, this is how capitalist markets work: things evolve and move forward, with growing greater good in aggregate. And this is how profit margins inevitably will decline.

Using microeconomic examples is a worthy exercise in order to extrapolate what should happen on the macro level. Who knows exactly when/where/how margins will decline, if they do. There is every reason to believe they will at least eventually regress towards the trend of the recent past, which is towards higher profit margins but at a more tepid pace than has been seen of late. Most importantly though, microeconomics teaches us how it is that margins contract when they do. High margins are an important component of the capitalist process. They are one of the most obvious factors which openly invites new market entrants, ultimately encouraging new investment and new hiring.

Disclosure: No position in any company mentioned in this post.