Michael Mauboussin on the Santa Fe Institute and Complex Adaptive Systems

/Michael Mauboussin of Credit Suisse is one of the best strategists on Wall Street and a thought leader who consistently introduces some of the most compelling topics to the financial community. It is therefore no surprise Mauboussin is now Chairman of the Board of Trustees at the Santa Fe Institute, an organization which specializes in the multi-disciplinary study of complex adaptive systems. I recently had the privilege of interviewing Mauboussin about his involvement with the Santa Fe Institute and his thoughts on complexity. Enjoy (and be sure to follow the links to some fascinating further readings):

Elliot: Now that you’re Chairman of the Board of Trustees at the Santa Fe Institute, what are your goals and visions for how to more broadly inject SFI’s lessons on complexity into the financial community’s understanding of markets?

Michael: In my role at SFI, the primary goal is to make sure that the Institute does, and can, do great science. The unifying theme is the study of complex adaptive systems. But the goal is to have a place where there’s support for important, transdisciplinary research.

That said, I would love to continue to see this type of thinking work its way into our understanding of financial markets. That is happening to some degree. One example is Andrew Lo’s work on the Adaptive Market Hypothesis. Another example is Blake LeBaron’s work on markets using agent-based models. I think it’s a more complete way of viewing markets than a standard rational agent model or the assumption of the absence of arbitrage. The problem is that modeling complex adaptive systems is a lot messier than those other approaches.

Elliot: When we last met at an event introducing The Success Equation to SFI members in New York, I asked you what the right “success equation” is for a young investor. Your response was to “keep coming to these events.” How did you first learn about the Santa Fe Institute? And how did you come to embrace the SFI?

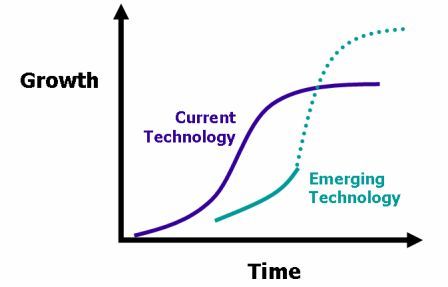

Michael: I first learned about SFI in 1995 at a Baltimore Orioles baseball game, where Bill Miller was my host and the proselytizer. He explained how this new research group dedicated to the study of complex systems was coming up with cool and useful insights about business and markets. Specifically, he was taken with Brian Arthur’s work on “increasing returns.” This work showed that under some conditions returns actually move sharply away from the mean. This is counter to classic microeconomic thinking that assumes returns are mean-reverting.

In many ways I was primed for the message. I had been doing a lot of reading, especially in the area of science, and so this way of thinking made sense to me from the beginning.

Elliot: Did you have a bias towards one market philosophy before you adopted the complex adaptive system mental model?

Michael: Although I had a solid liberal arts background before starting on Wall Street, I had very little background in business or finance. As a result, I had few preconceived notions of how things worked. It’s a challenge to come up with clear conclusions based on an observation of what happens in markets. On the one hand, you see clear evidence that some people do better than the indexes and that there are patterns of booms and crashes over the centuries. These suggest that markets are inefficient. On the other hand, there’s also clear evidence that it’s really hard to beat the market over time, and that the market is more prescient than the average investor. So for me, at least, there was an intellectual tug of war going on in my head.

I have to admit to being struck by the beauty of the efficient markets hypothesis as described by the economists at the University of Chicago. At the forefront of this, of course, was Eugene Fama, who recently won the Nobel Prize in part for his work in this area. What’s alluring about this approach is that it comes with a lot of mental models. You can equate risk with volatility. You can build portfolios that are optimal relative to your preference for risk. And so forth. Because you can assume that prices are an unbiased estimate of value, you can do a lot with it. The market’s amazing ability to impound information into prices impresses me to this day.

So it was with this mental tug of war as a backdrop that I learned about the idea of complex adaptive systems. Suddenly, it all clicked into place. A simple description of a complex adaptive system has three parts. First, there are heterogeneous agents. These can be ants in an ant colony, neurons in your brain, or investors in a market. Second, these agents interact leading to a process called “emergence.” The product of emergence is a global system that has properties and characteristics that can’t be divined solely by looking at the underlying agents. Reductionism doesn’t work.

What instantly drew me to this way of thinking is that it describes markets very well and it is very common in nature. The central beauty of this approach is that it provides some sense of when markets are likely to be efficient—in the classic sense—and when inefficiencies will creep in. Specifically, markets tend to be efficient when the agents operate in a truly heterogeneous fashion and the aggregation mechanism is working smoothly. Diversity is essential, both in nature and in markets, and the system has to be able to take advantage of that diversity. There are some neat examples in experimental economics to show how this works. It’s really wondrous.

On the flip side, when you lose diversity the system can become very inefficient. And that’s also what we see in markets—diversity loss leads to booms and crashes. Now the loss in diversity can be sociological, in which we all start to believe the same thing, or it can be technical, such as the winding up or winding down of a leverage cycle. But here we have a framework that accommodates the fact that markets are pretty darned good with the fact that they periodically go haywire. And SFI was at the center of this kind of thinking.

Elliot: It’s interesting that your answer on what theory of markets you subscribe to is not in the “black or white” vein whereby one must be in one camp and one camp only. It seems like much of the divisiveness in today’s discourse (in many arenas) stems from people’s unwillingness to see these kinds of shades of grey, though as you suggest, that mentality is not for everyone. Do you meet resistance from people when explaining your stance? Is there a way to get others to embrace “complexity” when people have an innate desire for linear, orderly explanations that are essentially either/or answers?

Michael: Most of us are uncomfortable with ambiguity—we’d rather just have a point of view and stick to it. But in markets, the real answer clearly lies between the folks who believe that markets are perfectly efficient and those who believe it’s largely inefficient. By the way, if you think the market is mostly inefficient there is no reason to participate because even if you have a sense that you are buying a dollar at a discount there is no assurance that the market will ever recognize that value. So some degree of market efficiency is essential even for those who believe that markets have inefficiencies.

My goal is less to get people to change their view and more to establish a better understanding of how things work. Once you learn about markets as a complex adaptive system and appreciate its implications, I find it difficult to go back to a more traditional point of view.

Elliot: In More Than You Know, you said, “The best way to describe how I feel following a SFI symposium is intellectually intoxicated.” Are there steps you take following these events to transform the ideas you’ve learned and the relationships you’ve built into expanding the scope of your own knowledgebase? And how are you able to harness this intoxication into productive output?

Michael: I wish I could be more systematic in this regard, but I think it’s fair to say that the ideas from SFI have permeated every aspect of my work. Perhaps a couple of examples will help make the point.

I’ve already mentioned conceptualizing markets as a complex adaptive system. This alone is a large step, because rather than simply moaning about the limitations of standard finance theory, you have a framework for thinking about what’s going on.

I’ve also already mentioned Brian Arthur’s work on increasing returns. Many businesses are being defined less by their specific market segment and more by the ecosystem they create. And it is often the case that in a battle of ecosystems, one will come out on top. So this set of steps provides a mental model to understand the process of increasing returns and, as important, how to identify them in real time.

Ideas from SFI have inspired my work in many other ways, from understanding power law distributions in social systems to network theory to collective decision making to the processes underlying innovation. I could go on. But suffice it to say that there is hardly an area of markets, business, or decision making where your thinking wouldn’t be improved by learning, and internalizing, the kinds of ideas coming out of the SFI.

Elliot: In More Than You Know, you also introduce Charlie Munger and SFI as “Two sources in particular [that] have inspired my thinking on diversity. The first is the mental-models approach to investing, tirelessly advocated by Berkshire Hathaway's Charlie Munger. The second is the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a New Mexico-based research community dedicated to multidisciplinary collaboration in pursuit of themes in the natural and social sciences.” It seems only natural that adopting Charlie Munger’s perspective to mental models would lead one to the SFI. Can you talk about the synergies between these two worldviews in making you a better analyst? What role did your adoption of Munger’s framework play in your attraction to the SFI?

Michael: Charlie Munger is a very successful businessman. Probably the first thing to note about him is that he reads constantly. He’s a learning machine. There’s bound to be a good outcome if you dedicate yourself to reading good stuff over a long period of time. That alone should be inspiring.

So as I think about the synergies between the worldviews, a few thoughts come to mind. First, it’s essential to provide your mind with good raw material. That means exposing yourself to a lot of disciplines and learning the key tenets. It also means spending time with people who think differently than you do.

Second, you have to be willing and able to make connections. What are the similarities between disease and idea propagation? What can an ant colony teach me about innovation? What do physical phenomena, such as earthquakes, tell us about social phenomena, such as stock market crashes? You need good raw material to make connections, but you also have to be careful to avoid superficial links.

Finally is the idea of thinking backwards. Munger is a big advocate for this. You observe that something is where it is: How did it get there? Why did it get there? There are some fascinating challenges in this regard right now. We know, for example, that the sizes of cities and companies follow power laws. Why? By what mechanism does this happen? No one really knows, and the prospect of solving those kinds of challenges is exciting.

But I have to finish with the point that this approach to the world is not for everyone. The interest or capability to work in this fashion is far from universal. So I wouldn’t recommend this to everybody. Rather, I would encourage it if you have a proclivity to think this way.

Elliot: You talk of a benefit of the mental models approach as having a diverse array of models that you can fit a given situation, rather than fitting a given situation to a one-size-fits-all model. Can you shed some insight on a) how you built up your quiver of models; b) how you organize these models (either mentally or tangibly); and c) how you choose which model to use in a given situation?

Michael: Yes, I think the metaphor is that of a toolbox. If you have one tool only, you’ll try to apply it to all of the problems you see. And we all know people who are just like that.

The mental models approach seeks to assemble a box with many tools. The idea is to learn the big ideas from many disciplines. What are the main ideas from psychology? Sociology? Linguistics? Anthropology? Biology? And on and on. In many cases you don’t have to be a deep expert to get leverage from a big idea. One of my favorite examples is evolution. Spend some time really understanding evolution. It is a mental model that applies broadly and provides insights that other approaches simply can’t.

I’m not sure I’m much of an example, but I have strived to read widely. This in part has been inspired by the people and ideas I have encountered at SFI. Most of my organization comes through writing or teaching. For me, that is a way to consolidate my understanding. If I can’t effectively write or teach something, I don’t understand it. Now I’m sure I write about things I don’t understand as well, but I try my best to represent the science as accurately as possible.

As for choosing the right model, the key there is to look for a fit. One concept that intrigues me is that nature has taken on and solved lots of hard problems, and there’s a lot we can learn from observing how nature works. So you might learn how to run a committee more effectively if you understand the basic workings of a honeybee colony. Or you might have insight about the resources your company should allocate to experimentation by examining ant foraging strategies.

The risk is that you take the wrong tool out of the toolbox. But I think that risk is a lot smaller than the risk of using the same tool over and over. I’ll also mention that the work of Phil Tetlock, a wonderful psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests that so-called “foxes,” people who know a little about a lot of topics, tend to be more effective forecasters than so-called “hedgehogs,” those with a single worldview. So not only is this an intellectually appealing way to go, there’s solid evidence that it’s useful in the real world.

Elliot: When you cite how Brian Arthur’s work “showed that under some conditions returns actually move sharply away from the mean. This is counter to classic microeconomic thinking that assumes returns are mean-reverting.” It makes me think about feedback loops and this passage from More Than You Know: “Negative feedback is a stabilizing factor, while positive feedback promotes change. Too much of either type of feedback can leave a system out of balance.” Positive feedback loops are seemingly the force that drives conditions away from the mean. How can we think about feedback loops in a more constructive way and are there steps that we can take to understand when/where/how they will appear? As a follow-up, is there a good mental model for thinking about when and how breakpoints appear in feedback loops?

Michael: There’s been a great deal written about this idea, albeit not necessarily using this exact language. One classic work on this is Everett Rogers’s book, Diffusion of Innovations. He was one of the first to describe how innovations—whether a new seed of corn or an idea—spread. From this a lot of other ideas emanated, including the idea of a tipping point, where momentum for diffusion accelerates.

The Polya urn model is also useful in this context. A basic version of the model starts with balls of two colors, say black and white, in an urn at some ratio. You then randomly select one ball, match it with a ball of the same color, and replace it. For example, say you started with 3 black balls and 3 white balls, so 50 percent of the balls are black. Now you draw a ball, observe that it’s black, and return it to the urn with an additional black ball. So the percentage of black balls is now 57 percent (4/7).

This urn model is very simple but demonstrates the principles behind positive feedback nicely. Specifically, it’s nearly impossible in advance to predict what’s going to happen, but once one color gets ahead sufficiently, it dominates the outcomes. (You can play a little more sophisticated version here.) It’s interesting to hit the simulator over and over to simply observe how the outcomes vary.

Another area where this model pops up is in format, or standard, wars. The classic example is Betamax versus VHS, but there are plenty of examples throughout history. Here again, as one standard gets ahead, positive feedback often kicks in and it wins the war.

Now I don’t think there’s any easy way to model positive feedback, but these are some of the mental models that may help one consider what’s going on.

Elliot: You talk about Munger’s advice to think backwards and invert. I think your first book was Expectations Investing which provided a framework for estimating the embedded assumptions in an equity’s price. Yet you also warn that this way of thinking isn’t for everyone. Was this something you realized after sharing the ideas with many or were you always aware of this? Do you have any ideas for why this has a relatively narrow audience? Is there a natural tie-in to the behavioral biases of humans and why this doesn’t work for everyone? (For example, the human proclivity towards the narrative bias to explain past events) And if so, how can we think backwards more rationally and overcome these biases?

Michael: Steven Crist, the well-known handicapper, has a line about horse race bettors in his essay, “Crist on Value,” that I love to repeat. He says, “The issue is not which horse in the race is the most likely winner, but which horse or horses are offering odds that exceed their actual chances of victory. This may sound elementary, and many players may think they are following this principle, but few actually do.” Take out the word “horse” and insert the word “stock” and you’ve captured the essence of the problem.

Our natural tendency is to buy what is doing well and to sell what is doing poorly. But as Crist emphasizes, it doesn’t really matter how fast the horse will run, it matters how fast the horse will run relative to the odds on the tote board. Great investors separate the fundamentals from the expectations, and average investors don’t. Most of us are average investors.

My advice, then, is to try to be very explicit about segregating the fundamentals and the expectations. Sometimes high expectations stocks are attractive because the company will do better still than what’s in the price. Great. That’s a buy. Sometimes there are stocks with low expectations that are dear because the company can’t even meet those beat down results. That’s called a value trap. So, constantly and diligently ask and answer the question, “what’s priced in?” Doing so is very helpful.