Biotech: Popping the Allegations of a Bubble

/There’s a popular view going around these days that biotech is in a bubble. Jim Grant was the first that I know of who publicly expressed this view, and he rationalized his argument asserting the Fed’s zero interest rate policy was distorting markets without even a cursory mention of the specific developments which have transpired in the biotech sector over the recent past. Several smart market participants who I respect greatly have echoed this perspective. I want to use this post to dispel that notion.

I’m a humanities, not science guy. I also am a generalist, not a biotech investor. I have some exposure to the sector and don’t plan to increase or decrease that exposure any time soon. That being said, I will leave the science vague and hope someone more knowledgeable and with more skin in the game can expand on this argument. As recently as the late 1980s, the drug discovery process was entirely centered around literally sifting through dirt in order to find molecules that may hold some therapeutic power. The science was simply a matter of “leaving no stone unturned” in a quest to find anything that just might work. In the late 1980s, there was a pivotal moment where drug discovery evolved to a process of learning how diseases and ailments operated on a molecular level and then working backwards via inversion to find proteins which could positively change the active mechanism of the problem. If you are interested in this development and its business effect, I strongly recommend the book Billion Dollar Molecule by Barry Werth.

Today we are undergoing another profound change and the catalyst was the mapping of the human genome. Not long ago, Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen debated whether there was real innovation happening in our economy today. Surprisingly not even Andreessen who took the “yes there is innovation” side of the debate even mentioned genomics and the impact it’s having on people’s lives around the world. The only real mention of biotech was Thiel’s complain about the FDA getting in the way too much, though if anything, this is not borne out by what has transpired these last few years. The problem for biotech is that its impact is very intangible compared to the Smartphones we all carry in our pockets everywhere. Genomics has greatly accelerated the process and efficiency of drug discovery. The results are evident, though people don’t see or feel it. In 2012 new drug approvals by the FDA hit a sixteen year high. Although 2013 did not see a new high in approvals, it did see the largest aggregate market opportunity for new approvals. I will oversimplify to make the point very clear: let’s say the average drug development timeframe was 10 years and has now accelerated to 5 years. Drug development inherently becomes worth more money if the time to earning first cash flows is cut in half.

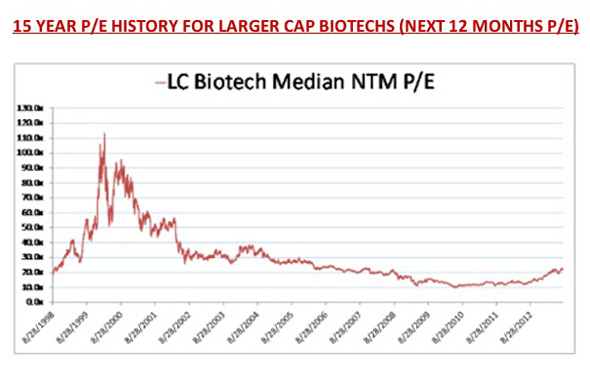

This above provides some justification for why “this time is different.” Things can be different and still a bubble though, so to try and further dispel this notion I want to point out two anecdotal examples for why the bubble assertion is wrong. Again I want to qualify that overvalued and/or overextended does not mean something is a bubble. For starters, let me borrow Robert Shiller’s definition of a bubble: (as paraphrased by me from Shiller’s panel at the Economist’s Buttonwood Gathering) a bubble is a price-mediated feedback between prices and market participants, with excessive enthusiasm, media participants, and regret from those who are not involved. The “psycho-economic phenomenon” is a defining characteristic that becomes ingrained in a culture and is related to long-term expectations that cannot be pinned down quantitatively. Let me offer the following chart, and you tell me where there's a bubble:

Simply put, we see none of this. Biotech has barely reentered the market participant’s conscious despite the big players returning to top line growth for the first time in years following their patent cliff. There are few if any stories in mainstream media about biotech billionaires at all. If you want to see hype, look no further than social media companies. Do we see anything remotely resembling an awareness in the masses that biotech has been a strong sector? I get asked all the time by clients about Tesla, Bitcoin, Twitter, etc., and I’ve never once been asked about biotech. And yes I think Tesla, Bitcoin, and Twitter prices comfortably fit Shiller’s definition of a bubble.

So let me offer two anecdotes on price and valuation in biotech to provide some context to this discussion.

1) Regeneron: In 1991 is considered common knowledge that Regeneron was a bubble, was insanely priced and was unsustainable. Here’s what the pundits were saying at the time (and do read that link for it's quite telling how similar the complaints are today): “Regeneron is a real long shot for investors: With no potential products even slated for clinical trials, the company is a good 10 to 12 years from delivering a marketable product…. ‘These are companies that have no product, and no prospect of revenue for three years or more. It only makes sense for them to make money when investors are in a feeding frenzy.’”

Fast-forward to today and an investor in Regeneron’s IPO is up ~1,789% in 23 years compared to ~390% for the S&P 500. This alone does not prove biotech is not a bubble but it highlights an important point that is fairly unique to this sector: even if you pay a high starting price, when you are right you will make multiples of your money. Simply put: bad investments in biotech will be worthless and successful investments will be worth multiples. The starting point matters little.

2) Incyte: This company is experiencing a wave of success, up a cool 207% over the past 52 weeks. Their first approved product, Jakafi earned $235.4 million in revenue in 2013 and is still growing today. In the pipeline, Incyte is working on one of the first treatments for pancreatic cancer which actually improves patient survivability. This first big spate of commercial success and big pipeline expansion would have a rational observer expecting this company to be way above record high levels, especially if we are in a bubble, right? Wrong.

In 1999 a shares of this stock were changing hands below today’s prices, though well above where INCY was upon earning its first real evenues. Back then there weren’t any signs of imminent success to be found. It’s definitely much easier to call something a bubble in hindsight, but the magnitude of the differences between then and now is striking. The fact that 1999 is still so fresh in many market participants’ memories is probably a powerful force in the proliferation of bubble assertions today.

Preclinical biotechs are valued based on odds of approval, the size of the market opportunity, the percent of the market the treatments can capture and discounted to today based on the time it will take to earn positive cash flow. It is unquestionably silly when biotechs surge in unison riding the wave of one company’s success. What happened in the wake of Intercept’s NASH primary endpoint success is not rational, and many companies did not deserve the pop they received. But that happens all the time in markets even when there is no bubble.

This is not a great time to pile into biotech, as some of these favorable developments discussed above have been reflected in prices. A bubble means run for shelter and seek cover, and that too is inappropriate right now. Something that is overextended is not necessarily also a bubble. It’s very possible, almost probable that biotech will go down 15% before going up from here. The fact of the matter is that biotech is the same as it ever was. The big boys are priced in-line with the market and have no premium attached to their multiple, and the small companies that investors get “right” will be worth multiples of what they are today, while the wrong ones will be worthless.

Thanks to my buddy who helped me pull this together so quickly today, you know who you are!

Disclosure: No position in any of the stocks mentioned, though a small portion of the portfolio is long specific biotech stocks.