Lucky to Live in this Era of Indexation

/Last week we were greeted with writings from two of the best investors and thought-leaders: Howard Marks of Oaktree and Murray Stahl of Horizon Kinetics. The decades of wisdom acquired by both Marks and Stahl now share with us youngens via these readings is a gift we must all take advantage of. I am about to grossly oversimplify the points from both of these greats in order to riff off of it into a point of my own. I give this warning both to preempt any complaints about my simplification, and as a suggestion to do yourself a favor and read what both of these gentlemen have to say before going one sentence further here. If you are kind and/or interest enough to return to this site, once done with those piece, please feel free to do so.

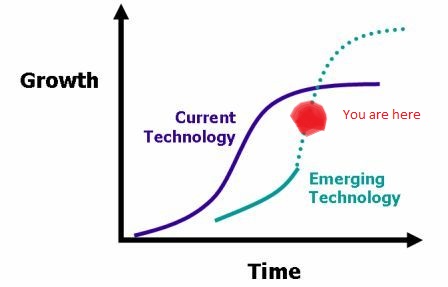

Since I received a link to Marks’ memo first, my evening reading started there and proceeded to Stahl’s piece. This was a fortunate coincidence. Marks lays out the case for the role luck plays in living life and attaining success in financial markets, tracing it to the idea markets are mostly efficient, but for those areas with a “lack of information…and competition.” Meanwhile, Stahl examines what he believes to be one of the single largest sources of market inefficiency today in what he calls “indexation.” After reading both pieces, I couldn’t help but think: “we are lucky to be investors in markets in this era of indexation.” This one thought struck me as the perfect conjunction between the two pieces.

Stahl has used the word “indexation” to explain the phenomenon whereby more assets and managers are investing in indices and ETFs which are designed to “provide portfolio exposure to very specific criteria, such as an asset class, an industry sub-sector, a growth metric, a stock market capitalization band, and so forth.” Over time, Stahl has discovered and invested in several of the inefficiencies resulting from such a phenomenon, including the “owner-operator” whose major stockholder manages the company, spin-offs designed to streamline business operations, etc. I recommend reading Stahl as to why these opportunities arise in today’s market.

Why do I say we are lucky to invest in this era of indexation? Because, as Stahl argues, indexation is an incredible source of market inefficiency. As more and more dollars seek out exposure in the broadest of ways, there is ample opportunity for those of us who seek to “turn over as many rocks as possible” to find the right opportunity. Two of my favorite setups fit this bill, although I never specifically delineated these ideas in writing as an outgrowth of indexation. This is so because both setups existed as long as there have been markets, and are in many respects traceable to behavioral traits of human beings. What has changed is that indexation provides a natural outlet through which these behavioral weaknesses are even more pronounced than in years past. I have named these setups “Guilty by Association” and “I’ve got a Label, but I don’t Subscribe.” While there are similarities between the two, they deserve to be thought about separately.

"Guilty by Association"

When a company is “Guilty by Association” they are treated in the same way as another, more identifiable peer group or index solely by some kind of perceived proximity. These tend to be situations that are more macro in nature, where a broader problem is reflected upon a specific company or sector. Some examples might be helpful.

During the crisis period in Europe, all European stocks were hit with equal force. The market “threw the good out with the bad” so-to-speak. One particular class of opportunities we spent considerable time on (and ultimately made significant investments in) was businesses listed in Europe, with a revenue base that was largely global. In other words, these were companies that traded in Europe, though they did the majority of their business outside of Europe itself. In these situations, there was selling, even from investors not situated in Europe, due to fears about the Eurozone’s viability. Yet, these companies themselves were in a position where if the Euro actually collapsed, they were unlikely to be significantly impacted in a negative way. In other words, they were “Guilty by Association” with the currency in which their shares were priced.

Another example would be the hatred of muni bonds in today’s environment. This entire asset class is hated due to concerns about Detroit’s bankruptcy and Puerto Rico’s solvency woes. Because Detroit and Puerto Rico are municipalities, conventional investment wisdom beholds that municipal bonds in the general sense must therefore be in trouble. This kind of extrapolation is abundant and wrong.

Indexation impacts these areas because people who invest in broad-based ETFs or indices sell their exposure entirely, in order to avoid the perceived fear. In doing so, the selling of the basket forces mechanical selling of all the subsidiary components without consideration for which specific constituents are and are not impacted on a fundamental level by the fear. Thus, the good that gets thrown out with the bad and is “guilty by association.”

"I've got a Label, but I don't Subscribe"

This is the micro twin of “guilty by association.” Since so much money is moving into ETFs, and ETFs are trading with all kinds of sector and niche labels, there is pressure to fit each and every company into some kind of cookie-cutter genre. These labels impact how analysts and investors alike think about specific companies. Stocks get assigned to analysts based on the “sector” they cover, and many investors invest in sectors or companies that are in accordance with a specific mandate. I had been planning a blog post for a while called “Beware of Labels,” but I think all of those points would better fit the context of this post. One of the biggest misnomers in today’s markets is the “technology” label. Mr. Market today dumbs "technology" down to mean: a) any company that is on the Internet; and/or, b) any company that makes hardware.

In my opinion, there simply is no such thing as an Internet company. There are retail companies who operate on the Internet (and at this point is there a single retail company who doesn’t operate on the Internet?), there are B2B companies who use the Internet to offer their services, there are financial platforms who provide web-based platforms. To ascribe the label “Internet” to one company and not another is merely referential of the fact that some companies are old and some companies are new. And even that is an oversimplification, for there are older Internet companies that are still called as much, despite being more analogous to marketing companies. And yet somehow, all these various, wide-ranging businesses end up with the “Technology” label despite the fact that their differences are far more pronounced and abundant than their similarities.

In a perfect world, we would throw away the technology label and call these companies what they are, whether that be media, retail, etc., but this isn’t a perfect world and that creates opportunities for us investors seeking out inefficiencies. Heck the “Telecommunications” sector is somehow a sub-sector of “Technology” and includes a company as old as AT&T (though I am aware AT&T today was actually one of the Baby Bells who ended up swallowing Mama whole). The biggest impact labeling has is in how analysts model these companies and the types of investors who are drawn to (or pushed away from) different sectors. We all know how popular comparables analysis and that too gets incredibly misleading when similarities and differences are conflated with one another.

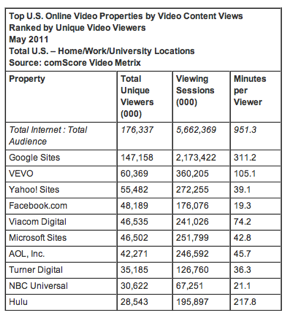

An example of this would be my investment experience with Google. Over the past few years, Mr. Market has called Google an “Internet stock” and a “one-trick-pony” at that. To that end, analysts and investors alike oversimplified in comparing Google only to other Internet stocks, and in a perceived battle against Apple, this same community viewed the company as out of its league (See GigaOM, CBS News and HBR on the "one-trick-pony"). I took a different perspective: Google is more akin to a media company whose advantage lies in the infrastructure and distribution side. Wikipedia describes media as “the storage and transmission channels or tools used to store and deliver information or data.” This certainly seems like an apropos description of Google, and it’s more clearly reflective of who pays Google money at the end of the day--advertisers, much like how we think about “traditional” media. If you think about Google this way, and realize one of the company’s crucial advantages is in how it stores, aggregates, categorizes and distributes information, it’s clear that Google does and can do far more things than “just” search. YouTube is a natural fit in this type of company, more so than just an Internet or search company, and as such, it leverages the advantages of Google’s platform while also leaving open the opportunity for Google to naturally segue into other areas altogether. Within that context, Google looks far less like a one-trick-pony, YouTube’s valuation becomes increasingly important (see my writeup on the importance of YouTube), and the company is in fact more diverse and capable beyond “just” search.

Labeling is a human endeavor; something we do in many disparate fields. One of the most well-known is the biological taxonomy (I think every adult still remembers “King Phillip came over for good spaghetti”), which is an organizational hierarchy. While labels have always been used in stock markets, only now are they actual forces behind the mechanical allocation of capital. This is so due to the proliferation of ETFs and “indexation.” Even in biology, there are blurred lines between different species, etc. This is but one reason why we have seen a great increase in spin-offs: when some companies who are thought of and thus modeled “that” way, have a subsidiary that doesn’t fit the bigger mold, that subsidiary tends to be “underappreciated” by Mr. Market.

Market Inefficiencies

A lot of people, myself included, like ripping on the Efficient Market Hypothesis. This is certainly not without merit; however, as Marks emphatically argues, there is much truth and wisdom in the idea that market participants are in fact really good at incorporating known information into the price of securities. When we look to make investments, we must then do what Marks’ implies in another of his spectacular memos, by asking ourselves “what is the mistake that makes this a mispriced investment opportunity?” With these two examples based on the problems associated with Stahl’s “indexation” we have two areas in the abstract within which we can identify mistakes. To that end, we are lucky to live in this era of indexation for how it exposes the market to repeatedly and mistakenly misvalue companies.

Disclosure: Long Google