The Panama Canal and why Public vs Private is the Wrong Debate

/This is the story of the financing behind what at separate points in time was once the world’s largest IPO and the largest real estate deal ever. Even more, this is the story about an undertaking which actually changed the course of world history. This is also the story of French capitalism and American socialism. Let me explain, drawing heavily from The Path Between the Seas, an excellent book, one I highly recommended, by David McCullough on the construction of the Panama Canal for the relevant history.

On November 17, 1869, the Suez Canal opened to remarkable fanfare. The event instantly made Ferdinand de Lesseps an international hero. de Lesseps work wasn’t done with this one accomplishment. To that end, he used his position of fame in order to attempt to conquer an even bigger task: building a canal to connect the Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean in Central America.

The Suez Canal had been built with private money and existed as a publicly held corporation (public as in freely liquid ownership amongst private citizens, not government ownership). de Lesseps saw the Central American project similarly, and felt its financing via private money was an important and “American” way to pursue the undertaking. Private financing was a strategic move, for at the time, the U.S. government still took the Monroe Doctrine declaring the Western Hemisphere the American domain very seriously. It was also a sentimental move which de Lesseps spoke about tying the importance of private capital with the notion that it would merely facilitate him as “but an executor of the American idea.” (McCullough, David (2001-10-27). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (Kindle Locations 1754-1757). Touchstone. Kindle Edition.)

This made sense on several levels. The U.S. stood to benefit substantially from the completion of a “path between the seas,” as the book bearing that title explains:

A Wall Street man named Frederick Kelley calculated that a canal through Central America could mean an annual saving to American trade as a whole of no less than $ 36,000,000— in reduced insurance , interest on cargoes, wear and tear on ships, wages, provisions, crews—and a total saving of all maritime nations of $ 48,000,000. This alone, he asserted, would be enough, irrespective of tolls, to pay for the entire canal in a few years, even if it were to cost as much as $ 100,000,000, a possibility almost no one foresaw. (Ibid, Kindle Locations 457-460)

Americans had plenty of experience with private capital invested in Panama. At one point, the Panama Railroad was the highest priced stock on the New York Stock Exchange, and its shares paid an average 15% dividend over its publicly traded period (here's a fun list of "amazing facts" on the Panama Railroad). When de Lessing commenced the Panama Canal project, it was to be the single largest financing in the history of the world, up to that point. Much was on the line alongside the money, including de Lessing’s legacy as a man who could build the impossible, and French pride as a global engineering powerhouse. Further, this was about capitalism and democracy, two ideas rapidly changing the world at that time, and the “limitless expectations associated with venture capitalism—pionnier capitalisme. The talk was of ‘the poetry of capitalism’ and of ‘the shareholders’ democracy.’”

As history would have it, the French, capitalist version of the Panama Canal wasn’t meant to be. For the French, the financial losses were drastic, as was society’s backlash. This is embodied in the aftermath of the Panama Canal Company’s failure, which today in France is known as “L’Affaire Panama.” Over 100 French legislators were accused of corruption and several governments collapsed. In the aftermath, anti-Semitism spiked sharply due to various conspiracy theories, ultimately climaxing in another French affair, “L’Affaire Dreyfus.”

Amidst the chaos in France, a successor to the Panama Canal Company was established in order to dispose of the company’s remaining assets, including its equipment, land rights, railroad ownership and digging completed to-date. The U.S. government emerged as the best, most logical buyer, eventually completing a deal with historic implications:

The purchase of the French holdings at Panama was the largest real-estate transaction in history until then. The Treasury warrant for $ 40,000,000 made out to “J. Pierpont Morgan & Company, New York City, Special Dispensing Agent,” was the largest yet issued by the government of the United States, the largest previous warrant having been for the $ 7,200,000 paid to Russia for Alaska in 1867. Participation by the house of Morgan had been agreed to by both the buyer and the seller and in late April, prior to receipt of the Treasury warrant, J. P. Morgan sailed for France to oversee the transaction personally. His bank shipped $ 18,000,000 in gold bullion to Paris, bought exchange on Paris for the balance, and paid the full sum into the Banque de France for the account of the Compagnie Nouvelle and the liquidator of the Compagnie Universelle. On May 2, at the offices of the Compagnie Nouvelle on the narrow, little Rue Louis-le-Grand, the deeds and bills of the sale were executed. On May 9 in New York the United States repaid the $ 40,000,000 to the house of Morgan. Morgan’s fee for services, charged to the Compagnie Nouvelle, was $ 35,000. With the $ 10,000,000 paid to Panama and the $ 40,000,000 to the Compagnie Nouvelle, the United States had spent more for the rights, privileges, and properties that went with the Canal Zone— an area roughly a third the size of Long Island— than for any actual territorial acquisition in its history, more than for the Louisiana Territory ($ 15,000,000), Alaska ($ 7,200,000), and the Philippines ($ 20,000,000) combined.” (Ibid, Kindle Locations 6847-6851)

Since this is the story of the financing of the construction of the canal, we’ll willfully ignore some of the “diplomacy” and its associated costs. The U.S. commenced construction in 1904 with the government overseeing a team of private contractors. One such contractor that emerged as an important American industrial power was Bucyrus Corporation (now part of Caterpillar). Bucyrus’ steam-shovels became the standard during the construction of the Canal and they did their job magnificently. A second contractor with massive success was the General Electric Company:

For the still young, still comparatively small General Electric Company the successful performance of all such apparatus, indeed the perfect efficiency of the entire electrical system, was of the utmost importance. This was not merely a very large government contract, the company’s first large government contract, but one that would attract worldwide attention. It was a chance like none other to display the virtues of electric power, to bring to bear the creative resources of the electrical engineer. The canal, declared one technical journal, would be a “monument to the electrical art.” It had been less than a year since the first factory in the United States had been electrified” (Ibid, Kindle Locations 10237-10242)

Unfortunately, the vast majority contractors the government hired couldn’t do their jobs all that efficiently. In 1907, the Army Corps of Engineers, under Major George Washington Goethals (yep that’s where the bridge got its name), took control of oversight and construction of the canal.

Let’s take a step back and think about where things were here. What started as a privately financed enterprise collapsed miserably, taking down the entire French economy and nearly the entire French empire with it. In the wake of this collapse, the American government took over the project and outsourced its completion to private contractors. Over three years, these private contractors failed to meet their deadlines, effectively forcing the U.S. government to take over the project entirely. When this happened, the military’s oversight of the project worked so well that some feared this would tip the U.S. towards socialism. These fears were discussed openly in prominent intellectual circles, with complaints like the following:

When these well paid, lightly worked, well and cheaply fed men return to their native land [warned a New York banker], they will form a powerful addition to the Socialist party . . . . By their votes and the enormous following they can rally to their standard they will force the government to take over the public utilities, if not all the large corporations , of the country. They will force the adoption of government standards of work, wages and cost of living as exemplified in the work on the Canal. Yet how could it be socialism, some pondered, when those in charge were all technical men and “little interested in political philosophy,” as one reporter commented. “The marvel is,” wrote this same man, “that even under administrators unfriendly or indifferent to Socialism , these socialistic experiments have succeeded— without exception.” (Ibid, Kindle Locations 9562-9568)

Instead there was to be no such thing as Socialism in America, but there are many lessons we can learn from today, here are just a few:

1) de Lesseps, the Frenchman behind their canal effort, was a figure reminiscent of the likes of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk for his capacity to “do the impossible” and change the world. Before de Lessep’s started the Panama Canal project he was a man who “could do no wrong.” People who buy into that mentality blindly, based not on sound economics, but rather a combination of nationalist pride and belief in an individual are setting themselves up for financial problems. This immense, almost super-natural belief in the capacity of French engineering to overcome all problems led to crucial blind-spots that Mother Nature exploited.

2) One of the decisive differences with the American and French efforts was William Gorgas’ initiative to rid the Canal Zone of malaria. Many viewed the fight against malaria and yellow fever as costly wastes of resources in an expensive undertaking. It was not without conflict that Gorgas was able to undertake his nearly “impossible” task of eradicating the mosquito-wrought region of these illnesses, yet without this colossal effort the Panama Canal itself would never have been built. For these cost-based concerns, a focus on public health was inconsequential to the private endeavor, until the problem became too severe and the entire project collapsed under this weight. Meanwhile, for a government to send its own emissaries to a region rife with deadly illness meant the potential for severe backlash from various groups. Truth be told, a healthy environment and a healthy workforce is crucial for large-scale successes.

3) The question of public vs private is the wrong one altogether, as efficiency matters first and foremost. The French went about the project privately. The U.S. went about it largely privately at first, and then with complete government oversight and execution. Today’s discourse here in the U.S. would have one believe the Americans are born capitalists and the French are born socialists, but that was not always true. American success happened independent of any public vs private debate, with both significant public and private rewards as a result.

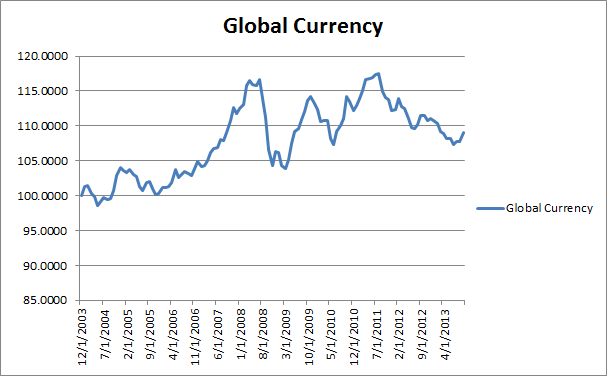

4) Public benefits are also private and vice versa. The completion of the Panama Canal had an unquestionably awesome effect on the rise of United States in the 20th century--both militaristically and commercially. But, even with the project under control of the U.S. government, American industry benefitted tremendously. This was a major catalyst in General Electric becoming the behemoth it is today.The Panama Canal was one project, and it alone helped the United States become the dominant global naval power. It is not an understatement to say that without the Panama Canal, American history would be decisively less grand. At the same time, American industry used the canal to buy and sell goods into the global market at an accelerating rate. Though its opening was followed by World War I, the Great Depression, the rise of protectionism and then World War II, so this commercial benefit of increasing global trade was not evident for decades down the line. Time and subsequent innovations were important factors in perceived failure turning to success. Today, as it undergoes its largest renovation to date in an attempt to double the volume of goods which can pass between the Atlantic and Pacific, the Panama Canal remains a vital artery for global trade and its benefits are enjoyed by both the public and private alike.